Cut-off canal celebrates 200 years

August 2018 - Everyone is preparing to celebrate what is being described as the 200th anniversary of the Lancaster Canal next year and now there is a coffee table book out to mark the event – even though the book itself makes clear that the canal was opened in instalments and 2019 marks the bicentenary of the opening of what is now the Northern Reaches. Peter Underwood has been reading it.

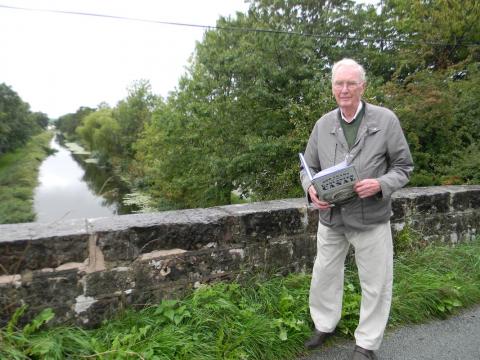

Author Gordon Biddle, now 90 years old, is probably best known to boaters with a taste for canal history as the co-author with Charles Hadfield of The Canals of North West England nearly 50 years ago. Around the same period he wrote a couple of books about the Leeds and Liverpool and Lancashire waterways.

Now he has returned from decades of writing about railway history to take a look at the Lanky and his painstaking research combines with the use of lots of historic pictures to paint a detailed picture of how this always-fractured waterway came into being.

From the first proposals the route fell into three sections, one south of the River Ribble at Preston to link with the Leeds and Liverpool, one lock free between Preston and Tewitfield, where the current navigable canal ends, and one between Tewitfield and Kendal, requiring lots of locks and at least one major tunnel.

It was nearly 30 years after the Duke of Bridgewater opened his canal, linking his mines to Manchester that the young engineer John Rennie produced a scheme, in Biddle’s words: “for a canal wide enough to take Mersey flats from Westhoughton ...”the 75 miles to Kendal.

By 1792 the first completed section from Preston to Tewitfield was officially declared open. By 1798 the canal south of Preston was open from Wigan, almost to Chorley, and extended to Johnson’s Hillocks the following year.

The problem was then to link the two southern sections across the valley of the River Ribble and there were various proposals, including an inclined plane a lock flights up and down to the river, linked by an aqueduct.

Eventually a tram-road was built to link the canal and opened on both sides of the river by 1804 – even though Rennie insisted it was a temporary measure. Of course, temporary can last a long time and a water route was never completed between the two southern sections, leaving the Lancaster completely isolated when the tram-road eventually closed.

So everything south of Tewitfield was opened an operational by 1804 and that left the route north to Kendal. There was much agitation from shareholders from Westmorland to get the work done. They were led by the Wakefield family who wanted the canal to serve their gunpowder mills at Sedgwick – a route necessitating the building of the now abandoned Hincaster Tunnel.

In a modern update, not touched upon by the book, a descendant of the Wakefields has been a vocal supporter of Colin Ogden’s group which was attempting to restore the Northern Reaches until Canal & River Trust shut them out this year.

It took another 15 years before the canal was finally opened to Kendal and it is that anniversary that will be celebrated in June next year. In fact the whole canal was not really complete for another six years which saw the building of the Glasson Branch, linking the Lancaster with the Port of Glasson.

A few short years later with the coming of the railways the Preston tram-road lost it’s importance and the Lancaster Canal Company sold it, concentrating on shipping good delivered by rail to Preston and on high speed packet boat services for passengers between Preston and Lancaster and beyond to Kendal. The service was so successful the canal company became one of the few to take over a railway – the Lancaster and Preston – although it was not terribly successful as a railway operator.

By World War 1 the canl was owned by the London, Midland & Scottish Railway and the closures began – first the last half mile to Canal Head in Kendal because of canal bed leaks, then in 1944 a bid to close the whole canal, which the local council and businesses opposed successfully.

In 1948 it was nationalised and the Docks and Inland Waterways executive was given permission in 1953 to close nearly six miles south of Kendal because of leaks through limestone cracks in the canal bed. Ten years on came the M6 and the last major section of the Lancaster to open was closed as the motorway cut through in six different places.

The Lancaster had always suffered from not being linked to the main system and, perhaps, it would have been more difficult to close the Northern Reaches in the 1960’s if it had been. In fact, it took until 2002 for the Ribble Link to be be connected – in the summer months at least – to the remainder of the network.

Despite being an early member of the Lancaster Canal Trust, and well aware of the early attempts to spare the canal from motorway builders, as well as the current situation, Gordon Biddle is not an optimist about restoration of the Northern Reaches, which he describes as ‘ambitious.’

He says: “… it seems on the face of it to be a very long term project costing well into eight figures.”

He goes on to point out that restorations in recent decades have been on canals linked to the main system. “The Lancaster, on the other hand, is a dead end canal, with only a tenuous connection to the main network...”

Asking himself, “Will it happen?” his downbeat answer is that, “Stranger things have happened.”

200 Years of the Lancaster Canal – an illustrated history. By Gordon Biddle. Published by Pen and Sword Books. £25.

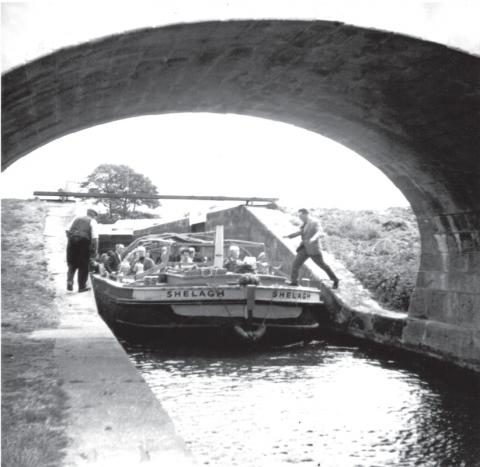

Photos: (1st) The book cover, (2nd) A day out in simpler times, (3rd) Locking on the Lanky, (4th) Author Gordon Biddle standing on Millness Bridge on the Northern Reaches, with his new book. Picture: Frank Sanderson.